CQ WEEKLY – COVER STORY

Feb. 25, 2012 – 3:38 p.m.

The Election’s Second Front

By Eliza Newlin Carney, CQ Staff

Eight months before Election Day, two hard-fought political battles are unfolding on the campaign trail — one highly visible, the other largely tactical.

|

||

|

The front-lines contest is between the candidates, political parties and well-funded super PACs mounting costly ads and public attacks. The second, less visible, war is over the mechanics of the election, and the rules that govern when and how voters will cast their ballots.

The ballot-box fight is grabbing fewer headlines, but it may prove crucial to the outcome of close races across the country. On the surface, the skirmish over voter lists, IDs and calendars looks very familiar: Republicans are issuing dire warnings about voter fraud, and Democrats are charging that voters will be disenfranchised. But this year’s war over voting is unprecedented in its intensity and implications. The stakes are high and the accusations shrill, and some even argue that the 2012 election could hang in the balance.

Triggered by a wave of largely GOP-written state laws that erect new barriers to voting on several fronts, the debate over ballot security versus voter access has erupted into a nationwide legal and political battle. The resulting lawsuits and countersuits are headed for the Supreme Court. And decades-old federal laws designed to protect voters from racial discrimination could be thrown out.

More than 20 state laws that impose new restrictions on voters, such as photo ID requirements and proof of citizenship, have alarmed Democrats on Capitol Hill and prompted the Justice Department to intervene. Civil rights activists warn that the new laws could block up to 5 million voters from the polls, more than enough to tilt the outcome in the event of a close election.

“The voting rights of African-Americans, Latinos and other progressive constituencies are under attack,” declared Wade Henderson, president and CEO of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. “In fact, I think we’re witnessing the most sophisticated, well-coordinated and sustained voter suppression campaign since the [1965] Voting Rights Act.”

Such warnings are probably overstated, say voting experts who note that both sides in the debate over voting lack hard evidence for their claims. Conservatives preoccupied with voter fraud have turned up few actual examples of voter impersonation at the polls. At the same time, civil rights advocates lack substantial evidence that voter ID laws significantly depress turnout.

“Much of the Republican rhetoric about voter fraud is more intended to excite the Republican electorate than to have a major effect on elections,” said Richard L. Hasen, a law and political science professor at the University of California, Irvine, and author of the forthcoming book “The Voting Wars: From Florida 2000 to the Next Election Meltdown.”

“Much of the language from Democrats about voter suppression seems to be similarly intended to boost voter turnout and act as a fundraising tool,” he said.

Politics aside, 2012 marks a turning point in American voting. Over the past century, most landmark voting laws have opened up access to the polls. Women (in 1920) were granted the right to vote; the Voting Rights Act outlawed racial discrimination at the polls; in 1971, 18-year-olds won the right to vote; the 1993 “Motor Voter” law allowed voters to register when obtaining a driver’s license.

More recently, the 2002 election law known as the Help America Vote Act helped states replace dilapidated voting machines. Enacted in the wake of the contested Florida recount that disrupted the 2000 presidential election, that law also pushed states to modernize and clean up their voter lists. A parade of states expanded windows for early and weekend voting, and

That trend reversed itself in 2010, following a GOP sweep in state legislatures and governors’ mansions. Eight states have enacted laws requiring voters to show a government-issued photo ID at the polls. (Two states — Georgia and Indiana — already had such laws in place.) Three states passed laws requiring voters to show proof of citizenship. Five eliminated or shortened their early-voting periods. Two states made it harder for non-government groups to register voters. In all, lawmakers in nearly three dozen states have introduced legislation requiring voters to show photo ID in order to vote.

The Election’s Second Front

“This really represents the first wave of restrictions of voting rights that we have seen in decades,” said Lawrence Norden, deputy director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University’s School of Law. “Really up until this year, with few exceptions here and there, the movement in this country has been to expand the franchise and make it easier to vote.”

Authors of these laws, mostly Republicans, counter that the measures are common-sense deterrents to fraud, are not aimed at disenfranchising voters and will increase voter confidence in elections.

Photo IDs are routine “if you want to cash a check, if you want to rent a movie, if you want to get on a plane,” said Missouri state Sen. Bill Stouffer, a Republican who sponsored a bill requiring a state voter ID ballot initiative that will go before voters this fall. “Everything we do in society — this is the [tool] that we use to prove we are who we are. It seems to me that protecting the ballot box with the same level of proof is not an overwhelming burden.”

The Ground War

|

||

|

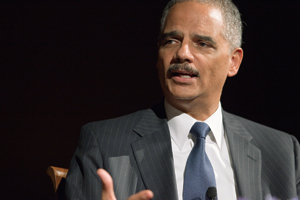

Several states, including Florida, Maine and Texas, have new voting rules pitting GOP state lawmakers against a Democratic administration. Under pressure from civil rights advocates and Democrats on Capitol Hill, Attorney General

But the states are fighting back hard. Holder intervened because Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act requires states with a history of discrimination to obtain pre-approval from the Justice Department before changing their voting procedures.

Now South Carolina has filed a lawsuit challenging the Justice Department’s rejection of its law and Section 5 itself. Texas has filed a similar, pre-emptive suit. Those challenges, along with similar suits filed in three other states, are headed inevitably for the Supreme Court, which has signaled that Section 5 may have outlived its usefulness.

“That’s really a cornerstone of voting rights and civil rights law,” Norden said of Section 5. “That could be bigger than all of this [state activity] in terms of affecting the landscape of voting rights in the United States.”

This year’s voting disputes are marked by partisan tensions, mistrust and emotional rhetoric on both sides. For Democrats and their allies, recent voter restrictions revive bitter memories of the poll taxes and literacy tests that divided the post-Reconstruction South.

The new laws, written with few exceptions by Republicans, reflect an “insidious” effort to “suppress the votes of people who the legislators think are not likely to vote for them,” said Laura W. Murphy, director of the Washington, D.C., legislative office of the American Civil Liberties Union, which has mounted a legal challenge to a new photo ID law in Wisconsin.

In Virginia, where controversial voting restrictions are moving through the General Assembly, former NAACP director Benjamin Chavis accused Republicans during a rally in Richmond last month of trying to “lynch democracy.”

The Rev. Al Sharpton, founder of the National Action Network, a civil rights group, organized a “march to protect our rights and the rights of our children” for March 4-9 to protest new state voting laws, retracing the steps of the 1965 voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. Civil rights organizers object not just to recently enacted photo ID laws but also to laws that shorten the window for early voting, require proof of citizenship, eliminate voting on the Sunday before Election Day and make it harder for third-party groups such as the League of Women Voters to mount registration drives.

The Election’s Second Front

In Florida, after legislators erected new hurdles to third-party groups signing up voters — requiring that forms be turned in within 48 hours of completion and imposing stiff fines for technical violations — the League suspended all registration activities in the state. The League also went to court to challenge the Florida law, has filed suit in Wisconsin, and intervened in lawsuits in South Carolina and Texas.

“It’s like death by a thousand cuts here,” said Elisabeth MacNamara, national president of the League. “Every one of these barriers makes it more and more difficult — not just for targeted voters, but for everyone — to vote.”

Opponents of the new laws point to data showing that they disproportionately affect minority, student, elderly, rural and disabled voters. Up to 25 percent of voting-age African-Americans do not have government-issued photo IDs, according to the Brennan Center, compared with only 8 percent of voting-age white citizens. Citizens older than 65 and earning less than $35,000 annually also are less likely to have photo IDs.

Minority voters also are far more likely to be registered through third-party groups than through government agencies, according to the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. Census Bureau data from Florida, for example, show that in 2008, more than 12 percent of both African-American and Latino voters registered through third-party drives, compared with just 6.3 percent of white voters. Minority voters also tend to turn out in larger numbers on the Sunday before Election Day, a practice now banned in Florida.

Civil rights activists have even accused GOP organizers of funding and orchestrating an effort to suppress the vote. They say the American Legislative Exchange Council, a well-financed conservative advocacy group, has circulated to states around the country model legislation to tighten voting rules. ALEC has denied any such effort, and Republicans argue that new registration rules, for one, will actually improve the system.

“This is not an attempt to prevent people from registering; it is an attempt to keep people from being disenfranchised,” said Hans A. von Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at the Heritage Foundation who manages the think tank’s Civil Justice Reform Initiative.

A Simmering Dispute

Some new state laws, said von Spakovsky, grew out of abuses by the now-defunct community group known as ACORN, which was notorious for dumping thousands of often error-riddled third-party registrations on election officials right before Election Day.

Recent clashes bring to a head a long-simmering dispute over the federal government’s proper role in election administration, said Doug Chapin, director of the Program for Excellence in Election Administration at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs in Minnesota. Even under the Help America Vote Act, state and local officials have remained largely in charge of running elections, both facilitating innovations and fueling controversies over inconsistent and sometimes spotty practices.

The seeds of this year’s new voting laws, argued Chapin, were planted in 1993, when the Motor Voter law — officially the National Voter Registration Act — rang GOP alarm bells over federal meddling and vulnerability to fraud.

“What Democrats see as a rollback, Republicans might see as more of a correction,” Chapin said.

State GOP officials also have seized on what some argue is a popular political issue, and not just for Republicans. Polls show that when it comes to voter ID, most Americans don’t see what all the fuss is about. A Rasmussen Reports poll found in December that 70 percent of likely U.S. voters believe voters should be required to show a photo ID such as a driver’s license before voting.

“Civil rights groups and the [Democratic National Committee] are out of touch with their constituents,” maintained von Spakovsky. “Because their constituents don’t think this is a problem.”

The Election’s Second Front

That’s proved a challenge for civil rights activists, who have labored to make the case that while the average American may have a photo ID, his or her grandmother may not. In Wisconsin, voters without IDs are caught in a Catch-22, as the state requires a birth certificate to obtain a government-issued ID, but now requires a photo ID from those who seek a birth certificate.

Fueling suspicion and anxiety on both sides are genuine problems with the nation’s balkanized, outdated voter registration system. A recent report by the Pew Center on the States blames outmoded registration systems for voter rolls riddled with inaccuracies.

About 24 million registrations — one in every eight — are no longer valid or are “significantly inaccurate,” the report found. More than 1.8 million deceased people turn up on the rolls as active voters, and another 2.8 million are actively registered in more than one state. Fully 24 percent of eligible voters, moreover, are not registered at all — about 51 million U.S. citizens, the report found.

“One of the things we believe is, if you reduce the inaccuracies on the lists, and also make them more complete, then you can tamp down some of that hyperpartisanship, and really start making policy based on research, data, good-government bases,” said David Becker, director of election initiatives at the Pew Center on the States.

Reliable data have been conspicuously missing from the highly charged debate over voting, on both sides of the aisle. A five-year Justice Department investigation under President George W. Bush aimed at uncovering voter fraud turned up scant evidence of organized voter fraud efforts. Republicans have engaged in a “sleight of hand” over the fraud debate, argues Hasen in “The Voting Wars,” conflating voter registration fraud, which tends to boil down to unintentional errors, with voter impersonation fraud, which is rare.

The Pew Center found plenty of problems with voter registration, noted Norden, but nothing to suggest voter fraud.

“It is not about a finding of fraud,” he stressed. “There is no evidence of fraud in this report. It’s about administrative inefficiencies and inaccuracies that can lead to problems for voters.”

Some fraud reports “do represent worrisome evidence,” according to an analysis by Loyola Law School professor Justin Levitt, but not of the type that voter ID rules would prevent. Levitt’s research has turned up incidences of fraudulent absentee ballots, efforts to coerce or buy votes, double voting, and attempts to tamper with voting machines, he testified at a congressional hearing last year.

But while such “forms of fraud do, sadly, exist,” Levitt concluded, they “are not as common as media attention may make them appear” and would not have been prevented by voter ID rules, which he likened to “amputating a foot to get rid of the flu.”

In fact, civil rights advocates and their allies can point to little hard research to support their claims that restrictive voter ID laws, for one, will block millions of voters from the polls. Evidence of bipartisan support for voter ID laws dates back to the 2005 Carter-Baker Commission on Federal Election Reform, which recommended photo IDs for voters, provided they were free.

In 2008, the Supreme Court rejected a constitutional challenge to Indiana’s voter ID law, concluding in part that the record submitted “does not provide any concrete evidence of the burden imposed on voters who currently lack photo identification.” The previous year, a survey of registered voters by American University’s Center for Democracy and Election Management concluded that only 1.2 percent of respondents lacked a government-issued photo ID.

Voter turnout actually went up after Georgia and Indiana enacted their voter ID laws, according to von Spakovsky. This was true both in 2008, when Obama drew thousands of first-time voters to the polls, and in 2010, he noted.

“I’m very skeptical, and I think there’s very little evidence that election laws and regulations have any impact on turnout,” said Chapin, of the Humphrey School. “People don’t really vote or not vote because of ID laws and polling-place hours and polling-place locations. They vote because of who’s on the ballot.”

The Election’s Second Front

Silver Linings

A plus side to recent voting debates, including the Justice Department’s challenge to South Carolina’s new law, is that they will bring some hard facts to the table, Chapin said. The November election will put the new laws to the test, and civil rights advocates said they will be watching closely.

In Crawford v. Marion County Election Board, the case upholding Indiana’s voter ID law, the high court left the door open to what’s known as an “as applied” challenge based on particular facts. Civil rights advocates are gathering that evidence, they said, in preparation to take their Indiana challenge back to the Supreme Court.

They’re also working in coalition and with grass-roots activists on several fronts. The ACLU, the League of Women Voters, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, along with other Latino and civil rights groups, have helped block proposed legislation in several states and mounted ballot initiatives to challenge new laws in others.

Voting rights advocates have also set out to educate voters on what tools they will need to qualify to cast ballots and to help them obtain the proper paperwork. They’ve turned to their Democratic allies on Capitol Hill, but partisan divides and GOP control of the House make any legislative fix unlikely. The only major voting-related bill on the table takes aim at deceptive practices, not voting restrictions. Still, Democrats in both chambers have moved to spotlight the issue.

“It has become an issue with our entire Democratic Caucus,” said Ohio Rep.

House Minority Whip

But the real focus has been on the Justice Department, which civil rights organizers complain was slow to respond. In December, Holder mollified his critics with a forceful speech in Austin, Texas, at the library of Lyndon B. Johnson, the president who signed the Voting Rights Act into law, and with his rejection of South Carolina’s voter ID requirement.

“There’s been a growing recognition that a failure to respond to these initiatives could have disastrous results in the 2012 election cycle,” said Henderson, of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. He called the wave of state voting laws “the sleeper civil and human rights issue of 2012.”

New voting laws enacted around the country will almost certainly have an impact on Election Day, legal experts say. Laws now taking effect will change the rules in battleground states including Florida, Ohio and Wisconsin.

If nothing else, the proliferation of new rules could confuse voters and will challenge election administrators in November. Perpetually underfunded to begin with, state election officials are contending with even greater budget shortfalls this year thanks to the economy. Newly drawn district lines could muddle things even further, landing some voters in the wrong polling places.

“This is a high-stakes election year at a time when just about every fundamental aspect of election administration is changing in a big way,” Chapin said. “The money that’s available, the rules of the game, the lines of the precincts — everything is changing.”

Some argue that the nation has yet to learn the lessons of Florida 2000, when ill-designed “butterfly ballots” and punch-card voting machines that left inscrutable hanging chads pulled back the curtain on a voting system badly in need of modernization.

The Election’s Second Front

The 2002 law made some improvements and helped quell controversies over voting machines. But election officials were slow to implement a key requirement of the act, namely that they develop computerized statewide voter registration databases. And a centerpiece of the law — an Election Assistance Commission to act as a clearinghouse for best practices — has now all but shut down, due to funding and administrative neglect.

The House last year passed legislation that would officially shutter the EAC. The bill’s author, Republican Rep.

“Those that know best, which would be the local and state officials, [have] looked at it and said: ‘This is something that is no longer needed,’ ” Harper said.

But the EAC’s virtual demise — the agency remains open but lacks a quorum to take action — bodes poorly for Election Day 2012, especially in the event of a close election, argued Hasen: “We are poised for a much worse election meltdown — worse than Florida — the next time there is a razor-thin election upon which the presidency depends.”

Whatever happens on Election Day, election experts and advocates say this year’s voting disputes create an opening for a more informed discussion about how to fix the voting system, particularly through registration improvements. The Pew Center is working with eight states on a model registration project that would make it easier for voters to register online and make better use of innovative data-matching technologies.

“It does, in a way, open the door for us to talk about what really needs to be done, and offer a counternarrative [about] what is really needed to protect the vote,” said Marcia Johnson-Blanco, co-director of the Voting Rights Project at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

In the meantime, the hot rhetoric, alarmist warnings and finger-pointing will continue — in the voting wars as well as in the candidates’ campaign.

Rebecca Shabad contributed to this story.

FOR FURTHER READING:

The House-passed elections bill is