CQ WEEKLY – IN FOCUS

Nov. 17, 2012 – 2:54 p.m.

Looking at the Real Legacy of Benghazi

By Emily Cadei and Tim Starks, CQ Staff

The election might be over, but Republicans picked up where they left off in their examination of the Sept. 11 attack against the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya. Sen.

|

||

|

But those questions are, for the most part, not likely to shed much light on what lawmakers insist is their ultimate aim: to prevent another Benghazi tragedy.

That might not, in the end, be possible — seasoned diplomats have noted in the aftermath of the attack that U.S. personnel working overseas inevitably accept a degree of risk if they’re doing their jobs properly. But there are plenty of issues, so far relegated to the sidelines, that Congress could explore to get a better grasp on how the United States can more safely and effectively deploy its diplomats, soldiers and spies in unstable parts of the globe.

The tension between safety on the one hand, and the need for diplomats and spies to be connected to locals speaks to a broader strategic question: What level of risk should officials be prepared to accept in order to accomplish U.S. aims in hot spots?

On this question, the Benghazi attack could spark a reassessment of the U.S. presence — military, diplomatic and intelligence — in the Middle East and North Africa.

Secret Mission

The investigation into the attack has been greatly complicated by the clandestine nature of U.S. presence in Libya. If anything, the Benghazi consulate turns out to have been a thin diplomatic veneer over a deeper and more active CIA presence. So on the tactical side, what first appeared to be a question of the State Department’s ability to protect its diplomats has become more of a question about the CIA’s security and the coordination — or lack thereof — between the spy agency and Foggy Bottom. Various reports since the attack have raised questions about which agency was primarily responsible for security at the consulate.

The aftermath also exposed gaps in one of Washington’s worst-kept secrets — the State Department’s long-standing practice of shielding CIA personnel under the guise of diplomatic cover. Two of the four men who died in the Benghazi attack were former Navy SEAL commandos who were reportedly CIA contractors operating under the guise of being State Department personnel. The CIA contingent there — which outnumbered diplomats — focused on countering terrorist threats and weapon proliferation, according to news reports.

“Everyone knows that both the State Department and the intelligence community work very closely together and have to work closely together, not just on the immediate security of American personnel at the embassies and in country, but on all kinds of other issues that affect the relationship between two countries,” says Sen.

“My experience is that there’s a lot of that that goes on,” Risch adds, but “as with all other operations, improvements always can be made.”

Jennifer Sims, a former deputy assistant secretary of State for intelligence coordination, however, says that in her experience, the diplomatic security wing of the State Department hasn’t coordinated as closely with spy agencies on threat assessments as it should have.

“That hasn’t always been done as smoothly and fluidly as one would like,” says Sims, now a senior fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. “Perhaps one answer would be to put a civilian in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to work in a way similar to how the military does it, where there’s an undersecretary for military intelligence.”

Looking at the Real Legacy of Benghazi

News reports on the CIA presence in Benghazi suggested there was an agreement between intelligence officials and Foggy Bottom for the CIA operatives in Benghazi to augment the diplomatic security there.

Sen.

“Well here’s what somebody needs to ask: If that were so, why did the people on the ground not know that?” he says.

It might have been more of a tacit assumption that the CIA, or what U.S. officials euphemistically refer to as the “Other Government Agency,” would provide some defense. “There clearly was an annex with other government personnel, and there were more of them and they were more heavily armed,” says retired diplomat James F. Jeffrey, who was the ambassador to Iraq until earlier this year.

One key question the State Department’s special review board will have to look into, Jeffrey says, is whether there were formal protocols or “an agreement in place for that element to support the embassy installation, and under what conditions and was it clear to everybody. That’s something we don’t know.”

Those questions speak to issues of coordination. But the events in Benghazi also raise questions about the wisdom of relying on the CIA as a security force in the first place. The agency is increasingly taking on those sorts of paramilitary or “muscle” operations — drone strikes are another high-profile example — and some experts say it is moving too far away from its traditional focus on intelligence collection.

Paul Pillar, a former senior CIA analyst now associated with Georgetown University’s Center for Security Studies, says that’s “a legitimate question to raise.” But he adds, “the loss of focus in that regard is not as severe as it may seem to us given the enormous attention devoted to things like lethal counterterrorism activities. The great majority of people and resources are still indeed devoted to those core missions of collecting and analyzing intelligence.”

Either way, the renewed emphasis on covert and paramilitary operations — encouraged by

Low Profile

|

||

|

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, some lawmakers focused on requests to the State Department from diplomats in Libya for additional security. The revelation of the CIA’s large presence in Benghazi helps explain why officials in Washington were so cagey in talking about beefing up diplomatic security. If security personnel had flooded into Benghazi, it would almost certainly have raised the visibility of American operations and drawn more scrutiny from locals.

The dynamic is similar to the impetus that drives State Department officials to try to “normalize” their operations in foreign countries — as they tried to do in Benghazi. They prefer to rely on local personnel rather than establish the sort of U.S. footprint that discomfits host populations already hostile to Americans.

Those priorities, however, are clearly in tension with efforts to safeguard civilian personnel. Libya is in many ways an extreme example in that regard — its security sector is in such disarray after its 2011 revolution that Tripoli simply cannot guarantee basic security for foreign embassies, as it is required to do under international obligations.

Looking at the Real Legacy of Benghazi

Jeffrey says he can think of only a handful of other locales in the world where that has recently been true — Yemen was headed that way earlier this year, but has since stabilized. “At times when we had presences in Somalia, that was similar,” he says. But he notes that the United States has long asked its diplomats and other civilian personnel to help it stabilize conflict and post-conflict zones. “The largest number of foreign services officers we lost were lost in Vietnam,” he says. “We have rows of them in our ‘wall of fallen.’”

In a Nov. 15 hearing on Benghazi, House Foreign Affairs Chairwoman

That includes, the Florida Republican said, conducting “realistic security assessments.”

Sims says it also requires bigger diplomatic security budgets. “Threats are going up to our embassies and consulates,” she says. “The idea that State or any bureaucracy is going to be able to be as agile as it needs to be without more resources is hard to imagine,” and moving “money from one consulate or embassy as threats spike isn’t going to be a long-term solution.”

Pillar agrees that “if you really wanted to properly protect every one of our installations from the possibility of these things, you would need security programs and budgets many, many more times than what we have.” But, he warns, “it would mean a major inhibition for individuals to do their jobs.”

In fact, the major fear cited by many career diplomats after the Benghazi attack is not for their own safety but of being hamstrung by overly restrictive security measures — particularly if they are determined by Washington rather than those on the ground.

Diplomats “are prepared to accept risk,” retired ambassador Ronald E. Neumann, president of the American Academy of Diplomacy, told the House Foreign Affairs Committee last week. “Not every risk is worth running, but neither can Americans diplomatic interests be achieved from behind walls and razor wire.”

‘Whole New World’

The Arab Spring-inspired revolutions and the resulting instability have created a particularly tricky operating environment for U.S. officials, who now must cope with untested governments, often with unreliable domestic security forces.

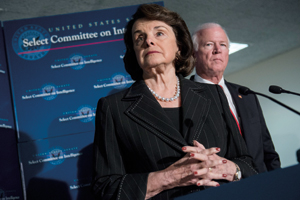

“It's a whole new world, and an extraordinarily difficult one,” says Senate Intelligence Chairwoman

Feinstein has promised that her committee will examine intelligence collection capabilities in the Middle East and North Africa, including funding and personnel levels. Like other branches of the federal government, the spy agencies have taken hits of roughly $5 billion to their budgets in the last two fiscal years.

But more money and personnel alone isn’t a cure-all, Pillar says.

“The turbulent and ever-changing and oft-hazardous environment in a place like Libya makes it difficult to be truly on top of every possible threat that could emerge,” he says.

Looking at the Real Legacy of Benghazi

The Defense Department is undergoing a similar reassessment of its capabilities in the region, amid cries from lawmakers about its failure to respond in a timely manner to help fend off the attackers in Benghazi.

A Pentagon timeline released earlier this month showed that military officials mobilized several different sets of special operations forces and military aircraft based in Spain, Germany and elsewhere in southern and central Europe to respond to the attack. None, however, arrived in time to be of any help.

That, as well as growing security issues in North Africa, have prompted the Defense Department to begin reassessing its force posture in the region, as well as the capabilities of its nascent Africa Command. Senate Armed Services members McCain, Graham and

“The threat level in North Africa and the Middle East has been rising for the past two years. And yet, on Sept. 11, al-Qaida-affiliated militants were able to mount a sophisticated assault lasting several hours against the U.S. consulate in Benghazi,” the three wrote in a recent letter to committee Chairman

The State Department, too, is struggling to develop a broad strategy for deploying its personnel and resources to better engage the region. U.S. diplomatic efforts are complicated by the security environment and frosty relations with increasingly powerful Islamists.

Tennessee Republican Sen.

At a fundamental level, however, the State Department needs to continue pursuing the same basic mission overseas that it has for decades, Jeffrey says. It’s a “very deeply held belief” among the diplomatic corps and at the top levels of the State Department and the White House, he says, that “we have to be on the ground not only reporting, but influencing events.”

Jennifer Scholtes contributed to this story.

FOR FURTHER READING: Diplomatic security, CQ Weekly, p. 2050; U.S. policy toward the Arab world, p. 1928; intelligence budget, 2011 CQ Weekly, p. 2673; Libya revolution, p. 2210.