CQ WEEKLY – IN FOCUS

Feb. 9, 2013 – 2:45 p.m.

The Pentagon’s GPS Problem

By Frank Oliveri, CQ Staff

|

||

|

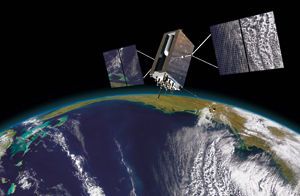

Signals from the U.S.military’s space-based Global Positioning System have been integrated into daily life and commerce, from cars to smartphones. If the satellites’ position, navigation and timing information suddenly disappeared, much of the global economy would be hobbled.

The armed forces are even more dependent. They use the GPS for almost everything that moves, from targeting bombs and coordinating fighter planes, warships, tanks and infantry to operating and guiding an increasingly important worldwide armada of aerial drones.

“We have a very heavy reliance on space and we consider GPS foundational in military operations,” says Gen. William L. Shelton, who heads the Air Force Space Command in Colorado Springs, Colo.

The GPS has been operating since the late 1970s, but it wasn’t until 2007, when China used a missile to destroy one of its own aging weather satellites in low-Earth orbit, that it became clear just how vulnerable the GPS is, both to other nations’ improving missiles and to relatively cheap jamming and hacking techniques. Another wake-up call could come soon, with reports that China is planning another anti-satellite test.

In recognition of these vulnerabilities — and the military’s overwhelming dependence on the GPS — the Pentagon and Congress in recent years have invested billions of dollars to develop new satellites with signals three times stronger than current models and with the capacity to exceed even that strength if necessary to override interference. The government also is investing in more sensitive and discriminating antennas and receivers, as well as a new encryption code, known as military code, or M-code, that would make it far more difficult to hack into the signals.

Such improvements will make the GPS more secure and more resilient, but they will not make the satellite network immune from attack. In an implicit recognition of the system’s vulnerability, the military is working hard to develop tactics and strategies for getting along without the GPS and other space assets for short periods.

“We may be asked to operate in areas where they may not have continuous command and control links, where our networks are under attack, where our space assets are under attack, not just by anti-satellite means, but by cyberspace or direct attack against our ground station — where freedom of action is going to be challenged,” says Mark Gunzinger, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, who, while at the Pentagon, wrote military directives that helped shape the planning for such eventualities.

The 2011 National Security Space Strategy, according to an unclassified summary, broadly laid out what the nation could do to prevent and deter such attacks, including teaming up with other countries on diplomacy, identifying attackers more accurately and, should deterrence fail, directly attacking those trying to disrupt the system.

The military also is trying to develop ground-based alternatives for delivering navigational signals.

Mounting Concerns

The fiscal 2013 defense policy bill completed in December authorizes $1.26 billion for investment in second- and third-generation GPS and new, more secure control terminals. But lawmakers also required the military to explain how it would function without the system — in “GPS-denied environments.”

Specifically, along with asking for descriptions of threats to the GPS, Congress directed the Defense Department to propose changes in tactics, techniques and procedures that would allow the armed forces to operate when the GPS and other space assets are “degraded or denied” for up to two months.

The Pentagon’s GPS Problem

The language results from evidence accumulating over several years that the military needs better preparation for a loss of the GPS. In April 2010, Robert J. Butler, the deputy assistant secretary of Defense for cyber and space policy, told the House Armed Services Committee that the results of a military exercise called “a day without space” were “stark.”

The results of that exercise were more ominous than that, according to Alison Brown, who runs NAVSYS Corp., which focuses on GPS technologies. The military, she says, “saw catastrophe” without the satellites.

Brown says the armed forces have been slow to react to their shortcomings, and, perhaps, have focused their resources too tightly on building more powerful satellites.

Indeed, many of the technological steps being taken to address weaknesses in the GPS chain are still “many, many years” from full deployment, Shelton says.

The M-code, for example, is on certain variants of GPS satellites, but the military has yet to integrate it fully into equipment that receives GPS signals. The first third-generation satellite is expected to launch in 2015. New receivers and antennas are slowly making their way into operation. “There’s a whole series of things that have to happen,” Shelton says.

Jamming and Spoofing

Even before China’s anti-satellite test in 2007, the U.S. military was worried that its enemies were seeking ways to cripple or disrupt the GPS.

In 2003, for example, U.S. officials announced that they had destroyed GPS jamming sites in Iraq. A year later, Air Force Secretary James G. Roche suggested that the Iraqi sites, which had been quickly neutralized, didn’t surprise the military.

“We had been waiting for this to happen and wondering when someone would finally do it,” he said at the time.

In addition to jamming, another form of attack is spoofing, which is a method of hacking into a GPS signal and altering the information it imparts.

A spoofing attack could, for example, fool fighter pilots or drones into believing they are somewhere different. The tactic involves broadcasting a slightly stronger signal than that received from the GPS satellites. It requires the exact location of the target, which is important because the GPS works by measuring the time it takes the signal to travel from satellite to receiver. The spoofing signal then slowly deviates to the hacker’s preferred course. Indeed, Iran’s capture of a U.S. military drone in 2011 is widely believed to have resulted from a spoofing attack where the drone pilot accidentally landed the plane in Iran, believing it was landing at its base in Afghanistan, according to reports.

Shelton said he believes the military has come up with solutions to address these weaknesses, as well as workarounds that would enable armed forces to function without the GPS.

The satellites fly in a medium-Earth orbit, roughly 12,552 miles in space, arranged so that at least four satellites are in view from virtually any point on the planet. The altitude and the number of GPS satellites in the constellation, Shelton says, make it exceedingly difficult for potential adversaries to attack them all directly.

The Pentagon’s GPS Problem

Shelton says the military also has taken steps to counter jammers. GPS signals are rather weak — think of a 40-watt bulb from more than 12,000 miles away — so jammers easily can project stronger signals than the satellites.

The military has sought to strengthen its signals using M-code and a third-generation GPS, senior military officials say.

They concede that the GPS still could be overpowered by a terrestrial signal. Shelton points out, however, that bigger jammers emit stronger, more detectable signals of their own that could make them easier for U.S. forces to locate and destroy.

The military also is working to secure the rest of the GPS communications chain. Antennas and receivers are being improved, for example, with newer receivers able to notify the user if the signal is being jammed.

In the end, military officials say they will need to take an all-of-the-above approach because the GPS and its associated technologies will become more vulnerable over time, sometimes with relatively simple jammers and other equipment.

“People have observed the American way of war for 20 years and we have enjoyed an impressive freedom of action,” Gunzinger says. “Our enemies will challenge freedom of operations in all those domains and some of those tools are not that expensive.”

FOR FURTHER READING: Fiscal 2013 defense authorization law (PL 112-239), CQ Weekly, p. 81; high demand for drones, 2012 CQ Weekly, p. 1968.