CQ WEEKLY – COVER STORY

March 8, 2014 – 10:24 p.m.

Will Taxable Groups Hide Political Cash?

By Eliza Newiln Carney, CQ Staff

Three Republican operatives who started an opposition research group after the 2012 election set out to emulate the success of a Democratic operation called American Bridge 21st Century, which captures the gaffes of GOP candidates on video and spins them into scathing commercials.

|

||

|

American Bridge had collected $17 million during the presidential race through its super PAC, which may raise and spend unlimited amounts independent of candidates, and an affiliated tax-exempt advocacy group. Its ads portraying Mitt Romney as a ruthless capitalist willing to “let Detroit go bankrupt” had thrown the GOP presidential nominee on the defensive.

But in fashioning their own Republican tracking operation, which they called America Rising, former Romney campaign manager Matt Rhoades and GOP organizers Tim Miller and Joe Pounder chose an unusual structure for a primarily political organization. Unlike its Democratic role model, America Rising operates principally as a limited liability company, or LLC — a type of hybrid business entity that is common in the broader business sphere but occupies an obscure and little-regulated niche in the world of politics.

LLCs give their owners the limited liability protection of corporations and the tax advantages of partnerships, and election lawyers say they are increasingly popular with political donors and organizers. It’s a trend that alarms independent political watchdogs. Intended principally for small companies with two or more owners, LLCs allow political organizers to operate almost completely outside of disclosure and campaign finance rules.

Unlike super PACs, which are not allowed to coordinate their activities with parties or candidates, a for-profit company need not keep politicians at arm’s length. And unlike politically active tax-exempt groups, which must publicly report their officers and grant recipients to the Internal Revenue Service, LLCs leave virtually no paper trail. With a little care they can avoid Federal Election Commission disclosures, public IRS filings and corporate taxes all at once — a dream come true, critics say, for publicity-shy big donors.

“It’s disturbing, because it seems like another, more airtight way to keep your donors out of sight,” says Sheila Krumholz, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan group that tracks and reports on political money.

A CRP investigation after the 2012 elections disclosed a complex, interlocking network of well-funded social-welfare groups and limited liability companies with links to the conservative billionaires Charles and David Koch. More than a half-dozen 501(c)(4) social-welfare groups, including Americans for Prosperity, which spent $122 million in the 2012 cycle, received hundreds of millions in contributions routed through limited liability companies with opaque names such as STN LLC, POFN LLC, and PRDIST LLC.

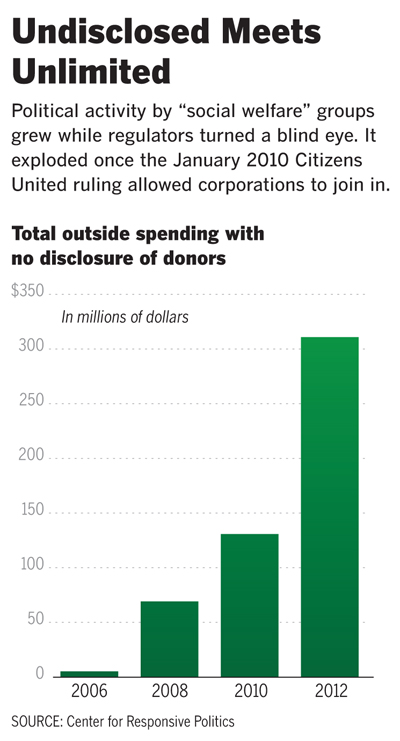

In the wake of the first presidential race since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United v. FEC ruling to deregulate political spending, public attention has focused on unrestricted super PACs and politically active tax-exempt groups. Social-welfare organizations, in particular, which operate outside the disclosure rules but spent hundreds of millions in 2012, are warring with the IRS on two fronts. The agency remains under investigation for its targeting of tea party and other groups, and its proposed fix has only intensified the uproar. The IRS has fielded a record 143,000 overwhelmingly critical comments from both conservatives and liberals in response to its draft regulations, issued in November, that would restrict political activity by tax-exempt organizations.

But for all the furor over social-welfare groups, political money may soon move to limited liability companies in any case, say election lawyers who are already trading notes on how such groups might set up shop. Driving the trend is Republican anger at the IRS, both for its past actions and its pending regulations, as well as the never-ending quest by political players to seek out less-regulated avenues of spending.

“Many of these groups are being formed intentionally in a very low-key way,” says Robert Kelner, who chairs the election law and political law practice group at Covington & Burling, an international business and corporate law firm. “So it may be a while before they become widely known and visible.”

But Kelner says numerous clients are approaching him with questions about how to organize themselves as for-profits, or as limited liability companies. They’re preparing for the possibility that the IRS will impose new political curbs on 501(c)(4) social-welfare groups, says Kelner. Even if the new IRS rules never take effect, conservative and tea party organizers, in particular, are convinced that the agency is on a partisan campaign to shut them down. IRS and administration officials say the agency’s mistakes in the tea party cases resulted from confusion and human error, not ill intent.

“There’s an increasing appetite to get out from under IRS scrutiny,” confirms Indiana election lawyer James Bopp Jr., who has led numerous constitutional challenges to campaign finance restrictions.

Will Taxable Groups Hide Political Cash?

Bopp and his Republican allies blame campaign finance limits, which they argue inevitably push political money into new avenues. After the 2002 McCain-Feingold law banned “soft” money donations to the political parties, hundreds of millions once raised by the parties shifted to outside groups such as 527 organizations, named for a section of the tax code. After the 2010 Citizens United v. FEC ruling, unrestricted super PACs soared. But both 527 groups and super PACs must disclose their donors, making non-disclosing social-welfare groups popular last year. Now IRS scrutiny of social welfare and other tax-exempt groups may propel money into for-profits.

“Regardless of whether these [IRS] rules die, there’s already a process that’s unfolding of deleveraging these social-welfare organizations,” says Kelner. “Money is beginning to flow away from them toward taxable vehicles.” Indeed, Kelner argues, “I think this whole kerfuffle about the proposed (c)(4) regulations is really an echo of the last war, rather than the next war.”

Uncharted Territory

The use of LLCs in politics is limited and little understood, and few IRS regulations exist that would explain how such groups might legally operate.

|

||

|

The phrases “for profit” and “tax exempt” are somewhat misleading. Whatever their tax designation, political organizations are in business not to make a profit but to distribute money from donors to help candidates.

Like a partnership, an LLC passes through tax liability to its individual members, rather than absorbing them like a corporation. A taxable LLC might avoid income taxes by designating money from donors as “gifts,” say some tax experts. But then big donors could be subject to a gift tax — something political players are at pains to avoid. Tax lawyers differ over whether a politically active LLC could avoid both income taxes and gift taxes at the same time, and the IRS has yet to weigh in on the topic.

“There is just very, very little ‘black letter’ to answer a lot of these questions,” says Joseph Birkenstock, a lawyer at Caplin & Drysdale, referring to the well-established case law or technical rules known as black-letter law. “You can’t flip to this court case or that audit.”

The few known limited liability companies active in the political sphere today appear to fall into one of two categories. The first is a quasi-political consulting firm, such as America Rising or the Democratic voter data firm known as Catalist, which make a minimal profit and exist to advance their respective parties’ candidates. The other is a pass-through organization that campaign finance watchdogs say operates as a “shell company” to disguise the identities of donors.

During the 2012 presidential campaign, a $1 million donation to the pro-Romney super PAC Restore Our Future, from an obscure company that identified itself as W Spann LLC, prompted a complaint from the watchdog groups Democracy 21 and the Campaign Legal Center to the FEC and the Justice Department. The two groups argued that the unnamed donor had set out to hide his identity through a shell company. Soon afterward, Edward Conard, a former executive with Romney’s old firm, Bain Capital, identified himself as the donor and said he had not intended to circumvent campaign finance law.

The same two watchdog groups lodged a complaint after the tea party group FreedomWorks for America received about $12 million from two limited liability companies known as Specialty Group, Inc. and Kingston Pike Development, LLC. Both were registered in Tennessee by Knoxville lawyer William S. Rose, who released a public statement saying that the donations were lawful but that he would not disclose their “secret.” The Washington Post later identified the donor as Illinois millionaire Richard J. Stephenson.

“Right now, wealthy individuals can use shell companies to spend millions in elections while evading disclosure requirements,” Rhode Island Democratic Sen.

Whitehouse joined a dozen fellow Democrats who sent comments to the Treasury urging the IRS to block such transfers through taxable groups in its new regulations.

Will Taxable Groups Hide Political Cash?

No Complaints

For-profit companies such as Catalist and America Rising have drawn no complaints of illegal activity from groups that favor the disclosure of campaign contributions, and organizers of both groups say their for-profit structure is straightforward and legal. Still, both organizations are carving out new territory in the world of campaign financing. Neither group faces any obligation to disclose its donors, and they face no prohibitions, as super PACs do, on working closely with candidates.

Launched in 2006 by veteran Democratic operative Harold Ickes, Catalist compiles data to help a large clientele of progressives with voter registration, voter contact and fundraising. Technically the group is a for-profit company run by a trust, consisting of 11 trustees. The group makes at most a “very modest” profit, and as a rule its receipts are plowed back into the company, says Laura Quinn, Catalist’s CEO.

“We don’t have a policy agenda; we don’t have a communications strategy; we are not talking to any audiences,” says Quinn. The group’s investors, she adds, “are clearly trying to support and create a company that provides core services across lots of progressive organizations at affordable prices.”

Similarly, the new GOP opposition research shop America Rising, unlike a conventional political consulting firm, is not out to make a profit but will reinvest all its profits back into the company, organizers say. America Rising does operate a super PAC, but that PAC raised only $475,000 in 2013, FEC records show, compared with some $1.3 million raised by America Rising LLC. One benefit of operating as an LLC is that America Rising can work in tandem with candidates and political parties interested in its research and videos, say organizers.

“With an LLC, you can have a client-based model that allows you to work directly with every group in the Republican Party, but also the conservative movement writ large, in order to provide research and tracking video to all of them,” says Miller of the America Rising super PAC.

Another benefit, Miller says, is that the group won’t get dragged into the controversy now swirling around 501(c)(4) social-welfare groups, whose future on the political scene has become uncertain.

“The IRS scandal had flared up, and the scrutiny of the Obama administration on conservative (c)(4)s and nonprofits was a red flag for us,” says Miller, describing why the group chose the LLC structure. Another factor, he adds, was “the unknowables when it comes to new (c)(4) rules and how that might impact a group like ours that does a lot of political work.”

The Next Generation?

It’s too early to say whether a flood of organizations is rushing to reinvent themselves as for-profit companies in the model of Catalist, America Rising, or more obscure companies such as W Spann or Kingston Pike. Some election lawyers say it’s more likely that organizers will reconfigure their groups as trade associations, which register with the IRS under section 501(c)(6) of the tax code.

|

||

|

Indeed, two years ago the leading Koch-linked political operation doling out grants to a network of conservative tax-exempt groups was a social-welfare organization known as TC4 Trust, according to the Center for Responsive Politics’ investigation.

Now TC4 Trust has closed up shop, and the new sugar daddy at the heart of the Koch network is a trade group called Freedom Partners Chamber of Commerce. Freedom Partners gave $235.7 million in grants between late 2011 and late 2012 to nearly three dozen groups, tax records show. Much of the money was routed through LLCs to Americans for Prosperity and other campaign-focused social welfare organizations.

Will Taxable Groups Hide Political Cash?

“We were established as a (c)(6) because we advance our members’ common business interests,” says Freedom Partners spokesman James Davis. The trade group has more than 200 members who pay membership dues starting at $100,000, says Davis, who described the group’s activities as “coalition building and policy analysis, research that we provide to a broad coalition of groups that are advancing our business members’ interests.”

GOP election lawyer Cleta Mitchell, of Foley & Lardner, acknowledges that her clients are extremely worried about the pending IRS regulations, which will be subject to at least one public hearing and a contentious and drawn-out rule-making process. The agency was responding to criticism on the right over its targeting of tea party groups, and on the left over its failure to curb undisclosed political spending by 501(c)(4) tax-exempt groups. But Mitchell says she’s advising political organizers to wait and see before making big changes.

“They come to me and they’re panicked,” says Mitchell, who says clients are asking: “‘What are we going to do if these become law?’ I’ve told everybody I’m not going to talk about that, my focus is on stopping this” set of regulations from taking effect.

Similarly, Republican election lawyer Jan Baran of Wiley Rein says the environment is so unsettled that he doesn’t expect a sea change any time soon. While LLCs are an option for political players, he argues, they are “a costly option” given the possibility that donors would have to pay gift taxes, or companies would face income taxes.

“Nobody’s doing anything for the time being,” says Baran. “These rules are certainly not going to be finalized this year, if ever. And I don’t think anybody’s going to make plans until there is more certainty about the type of rule change, if any, that is going to occur.”

But Baran acknowledges that political money has a way of circumventing new restrictions, whatever form they take: “We have learned one thing, which is that money doesn’t stay static. It does pop up elsewhere if the rules change, whether its tax rules or FEC regulations or legislation.”

Some campaign finance and tax experts predict that taxable groups will be the next to pop up, and that their growing use in campaigns will prove even more vexing to the IRS than the role played by politically active social-welfare groups. In public comments submitted to the Treasury Department on the proposed IRS regulations, law professors Brian D. Galle of Boston College and Donald Tobin of Ohio State University warned the IRS explicitly to forestall the proliferation of taxable groups.

“Absent further clarification of the tax treatment of taxable entities involved in campaigns, there is significant risk that organizations will forgo tax-exempt status and instead organize as taxable organizations,” the law professors wrote.

“At this moment,” they went on, “it is not clear what the tax ramifications would be to a taxable organization involved in campaign advocacy. Without further clarification by the IRS, taxable organizations may be the next vehicle of choice to avoid campaign finance disclosure, and may once again embroil the IRS in unnecessary political decisions.”

The Business of Politics

Political activists and contributors are beginning to explore establishing themselves as private businesses, such as limited liability companies, a legal structure that allows them to avoid the restrictions and disclosures imposed on traditional political committees. Taxable business entities generally take one of four forms: a sole proprietorship, a partnership, a corporation or a limited liability company.

Sole proprietorship: One owner runs a sole proprietorship, receives all the profit, pays the taxes and is responsible for the bills. If the company is sued or goes into debt, the owner is solely liable.

Partnership: Two or more people make up a partnership. As in a sole proprietorship, the partners are liable in the event of lawsuits or losses. Profits are “passed through” to the partners, who pay taxes on them on their individual tax returns.

Will Taxable Groups Hide Political Cash?

Corporation: A for-profit corporation is a legal entity separate from its owners, who are shareholders. Shareholders are not personally liable for the corporation’s losses, debts or legal obligations.

Limited liability company: An LLC’s owners enjoy the same protections from liability as corporate shareholders. But like partnerships, LLCs allow pass-through taxation: their owners report profits or losses on their own tax returns.

FOR FURTHER READING: When a corporation becomes a person, CQ Weekly, p. 246; politically active tax exempt groups, 2013 CQ Weekly, p. 2030; Citizens United ruling, 2010 Almanac, p. 11-35.