CQ WEEKLY – COVER STORY

April 29, 2014 – 9:12 a.m.

'Max PACs' Poised to Exploit Supreme Court Decision on Campaign Finance

By Eliza Newlin Carney, CQ Staff

Within a week of the Supreme Court’s April 2 ruling to relax limits on campaign contributions, top Republican Party officials unveiled a new special fundraising account that is now free to collect six-figure checks for the first time.

|

||

|

The Republican Victory Fund brings together the three major GOP committees backing presidential, House and Senate candidates, and it positions them to take full advantage of the ruling known as McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission. The fund is one of more than a half-dozen similar committees, all featuring multiple players raising big money together, that have sprung up since the decision.

Officially known as joint fundraising committees, such share-the-kitty accounts may soon become the “super” campaign funds of political rainmaking, thanks to the McCutcheon decision.

Joint accounts have long allowed party committees and candidates to band together to round up large checks and divvy them up among themselves, mostly under the radar. But the McCutcheon ruling canceled the aggregate limit that had barred any single donor from giving more than $123,200 to candidates and parties collectively in an election cycle. Striking that cap frees the largest joint fundraising committees to collect checks as large as $3.6 million from a single contributor who wanted to give the legal maximum to national and state party committees and to each and every one of the party’s federal candidates.

This huge increase will give candidates and parties much more clout to compete with outside groups that face no limits and don’t always have to disclose their donors. The collective fundraising accounts have been tagged with nicknames such as “jumbo” joint committees and “max PACs” and are notorious for spotty disclosure and lax oversight. They also have a history of rewarding big donors with exclusive junkets and private meetings with elected officials.

“I think McCutcheon is a real turning point in our debate about money in politics,” Sen.

Senate Democrats have pledged to vote this year on a constitutional amendment to reverse such Supreme Court rulings as McCutcheon v. FEC and others that have rolled back the political money limits. Advocates of campaign finance restrictions argue that the ruling will effectively bring back soft money, the unlimited contributions to political parties that Congress banned in 2002.

|

||

|

Justice

More than 350 joint fundraising committees are registered with the FEC, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, some bearing catchy names such as Western Women Win and Patriot Day. Many of those divide cash between party committees, or between individual candidates numbering from two to several dozen.

The Republican leader in the Senate,

Election lawyer Robert Kelner predicts that such joint committees will now attract even more lawmakers, and will “empower whoever is in a position to assemble high net-worth donors to fund that committee.”

'Max PACs' Poised to Exploit Supreme Court Decision on Campaign Finance

“If you are a committee chairman or a member of the leadership,” Kelner says, “you’ll be in a position to establish the world’s most powerful leadership PAC in the form of a joint fundraising committee.”

A Bigger Kitty

The McCutcheon ruling does not free politicians to pocket larger checks for their individual war chests, however. The court left standing the “base” contribution limit for what a single donor may give any one candidate or party committee. That limit is $5,200 to a candidate and $64,800 to a party committee in an election cycle.

|

||

|

But the new rules will let party leaders and candidates solicit far larger checks for their joint accounts. Though no one candidate may get a share of the kitty larger than $5,200, the kitty itself will be much bigger — and so will the contributions put into it.

That’s because the now-defunct aggregate limits had effectively blocked any one donor from giving the maximum to more than nine candidates or two major party committees in one election cycle. No campaign contributor was permitted to give more than $48,600 to candidates as a group, for example, or $74,600 collectively to parties — a combined total of $123,200.

Now donors are free to “max out” to as many candidates and party committees as they like. On the day of the McCutcheon decision, Fred Wertheimer, the president of the advocacy group Democracy 21 who for decades has campaigned for tighter limits on political money-raising, said the ruling’s upshot would be that “joint fundraising committees are going to be the vehicle for raising million-dollar and $2 million and $3 million contributions.”

Some lobbyists bemoan the barrage of money-seeking requests that is already hitting them. But party leaders and candidates have seized quickly on the chance to raise more and bigger checks for their multiplayer accounts.

The 2014 Senators Classic joint committee, for one, registered with the FEC on April 14, and will divide its haul between 19 GOP Senate candidates, each eligible for the $5,200 maximum check. Instead of writing 19 checks for $5,200 apiece, a donor to Senators Classic may write a single one for just under $100,000 — nineteen times the base contribution limit.

Similarly, a new joint campaign fund for five Democratic senators dubbed Secure Our Senate can collect checks as large as $26,000 — five times $5,200. And the Republican Victory Fund, the committee formed days after the ruling, may ask any donor for $129,600 at a time, combining the money-raising firepower of the Republican National Committee, the National Republican Senatorial Committee and the National Republican Congressional Committee. (The old rules would have capped that check at $74,600.)

Campaign watchdogs warn that billionaire mega-donors, already buoyed by the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United v. FEC ruling to deregulate independent campaign spending, can now use the joint committees as another route to dominate campaigns still further.

In McCutcheon v. FEC, Chief Justice

But a McCutcheon amicus brief submitted by House Democrats

'Max PACs' Poised to Exploit Supreme Court Decision on Campaign Finance

Sharing the Wealth

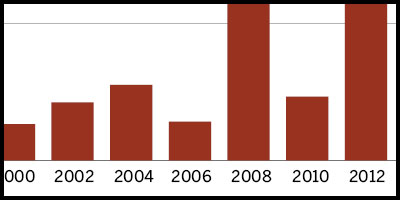

Joint fundraising committees have existed since the late 1970s, but didn’t become popular until 2000, about the same time that unlimited soft-money fundraising hit its peak. In 1990, just eight joint committees raised $3.9 million between them, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. In 2000, a full 105 joint accounts pulled in more than 10 times that, or $52.6 million.

|

||

|

That was just the start. By the 2012 elections, 473 such committees collectively raised $1 billion, boosted largely by the joint “Victory” funds run by President

In this election cycle, House Speaker

The House majority leader, Virginia Republican

For this midterm, Republicans have raised almost four times more through joint campaign accounts than have Democrats. GOP joint receipts total $23.3 million so far, compared with $6.3 million for Democrats, according to the Sunlight Foundation, a research group that promotes government transparency. This disparity may be because Democratic Party committees have outpaced their GOP counterparts in low-dollar fundraising, while Republicans have relied more on big donors, who are often the target of joint fundraising events.

But Democrats have their own lucrative joint accounts. The House Senate Victory Fund has netted $2.6 million in this cycle to divvy up between the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, with an assist from the party’s chief fundraiser, Obama.

Obama starred at an exclusive April 9 dinner for the fund seven days after the McCutcheon ruling, a dinner held at the home of Houston trial lawyer and philanthropist John Eddie Williams and his wife, Sheridan Williams. Also in attendance were Rep.

Obama, Reid and Pelosi were scheduled for a repeat performance on May 7 at the Los Angeles home of Walt Disney Studios Chairman Alan Horn and his wife, environmental advocate Cindy Horn, at an event costing $65,000 per couple. High-flying donors to the House Senate Victory Fund include billionaire James R. Crane, CEO of Crane Capital Group, and Kase Lawal, CEO of the Houston oil and gas company Camac Energy Inc.

Rewards and Workarounds

As with all high-dollar campaign money-raising, the top donors to joint campaign committees invariably enjoy special rewards for their largesse, from ski retreats, golf getaways and private receptions to photo ops and telephone conference calls. GOP leaders are reportedly drawing up a list of such benefits to entice top donors to the new Republican Victory Fund.

|

||

|

'Max PACs' Poised to Exploit Supreme Court Decision on Campaign Finance

A joint fundraising event last year between Boehner and Sen.

“These joint fundraising committees are going to be in the name of Boehner and Reid and Pelosi and McConnell, and whoever the presidential candidates are,” says Craig Holman, government affairs lobbyist for the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen. “That’s what’s going to make these the vehicles of choice for those who want to throw money at the feet of those who legislate [for] them.”

Joint committees also allow lawmakers to leverage their relationships with donors by bringing together politicians whose fans have given them the maximum, but who may still give freely to other elected officials. Many joint campaign funds include lawmakers from widely separated regions of the country, inviting “maxed-out” contributors in Los Angeles, for example, to keep writing checks to like-minded candidates in New York.

“Most frequently, it’s just two members exchanging their donors,” says election lawyer Brett Kappel, counsel in the government relations and political law practice groups at the Arent Fox law firm. “You’ll have a senator from the West Coast and a senator from the East Coast, and they host an event that is supposed to benefit each of them.”

The Colorado New Hampshire Victory Fund, for example, has split most of its $25,500 between Democratic Sens.

The money raised and spent by such accounts can be hard to trace, as candidates don’t always follow the FEC’s elaborate reporting rules for joint fundraising, and the commission, evenly split and stalemated between Republican and Democratic appointees, is not rigorous about enforcement.

The agency fined Florida Republican Sen. Mel Martinez $99,000 in 2008 for failing to properly report the money raised by four joint fundraising committees; Martinez resigned his seat a year later. The FEC also imposed a $6,500 fine in 2006 on Sen. Rick Santorum, a Pennsylvania Republican, for a similar reporting violation. Santorum lost his seat the same year.

These days, the FEC routinely sends out letters citing candidates for failing to properly disclose their joint fundraising agreements and receipts, but fines are rare. In April alone, three such letters went out to the campaigns of House Republicans

Even the newly registered Democratic Secure Our Senate 2014 account managed to botch its statement of organization, failing to identify itself as a joint fundraising committee as required, the FEC wrote the group’s treasurer on April 24. Secure Our Senate organizers did not respond to a request for comment.

“These are ephemeral committees,” Kappel says. “They’re formed; they hold one event; they go out of business.” He maintains that disclosure rules have “been a big problem ever since joint fundraising committees came into vogue.”

Some argue that the FEC’s burdensome reporting rules for joint committees make it unlikely that such accounts will take off after all. GOP election lawyer Dan Backer, who helped instigate the McCutcheon v. FEC challenge, says the required contracts, allocation formulas and exhaustive public disclosures make such committees “a massive pain in the [behind]” for election lawyers.

Backer should know. He runs a joint campaign account dubbed Freshman Hold ’Em that split $192,166 between 31 House Republicans for the 2012 elections. In this election, Freshman Hold ’Em is splitting its take between 15 GOP House members, including

Backer argues that super PACs will remain a bigger draw for top-tier political donors than joint campaign funds. A big donor can have a say in how super PAC money is spent, he notes, but cannot control dollars given to joint, party and candidate accounts.

'Max PACs' Poised to Exploit Supreme Court Decision on Campaign Finance

“People who are serious donors are doing so because they want to advance a philosophical or policy-oriented agenda,” says Backer, who maintains that super PACs offer that opportunity.

Some dismiss watchdogs’ dire warnings that the McCutcheon ruling will revive the soft-money days, when lawmakers trolled for multimillion-dollar contributions in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street to deliver to the political parties. The extra layer of reporting imposed on joint fundraising committees is designed to improve transparency and accountability, says Democratic election lawyer Marc Elias.

“It’s not soft money,” Elias declares. “There are definitions in the law that make it clear it’s not soft money. It is, by definition, hard money because it is subject to reporting requirements and limits in the law.”

Finding a Fix?

But even if lawmakers deposit six-figure contributions into joint accounts and not into their personal campaign war chests, members of Congress who solicit super-sized checks from people with business before them run the risk of appearance problems. The McCutcheon ruling may put members of Congress in danger of “being dragged into corruption investigations,” Political MoneyLine’s Kent Cooper noted recently in Roll Call.

|

||

|

Chief Justice Roberts responded to corruption concerns in his McCutcheon opinion by suggesting that Congress could take steps to prevent it. Congress could restrict transfers among candidates and political committees, he proposed, or require that donations beyond the old aggregate limit “be deposited into separate, nontransferable accounts and spent only by their recipients.”

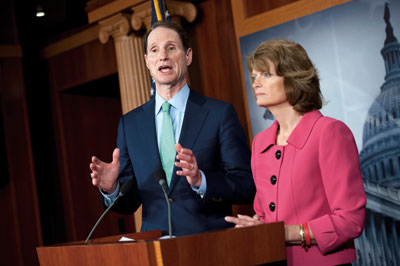

Senate Democrats have launched hearings in the wake of the McCutcheon ruling. The Senate Rules and Administration Committee on April 30 took up a new disclosure bill sponsored by

“If you follow the series of Supreme Court rulings, from Citizens United to McCutcheon, the clear implication is that the Supreme Court says that money is speech, and that therefore limitations on that speech are going to be hard to sustain” says King. “Consequently, to me, the only avenue left to have any responsibility in this area is disclosure.”

But the Senate has repeatedly rejected a disclosure bill written by Democrats, and the prospect that bitterly divided lawmakers will come together on anything as contentious as campaign finance changes appears dim at best.

Some say that joint campaign funds will not turn out to be the “super” committees that many foresee in the wake of the McCutcheon ruling. Wealthy donors may not want to give up the luxury of writing checks anonymously to politically active tax-exempt groups, for example, which operate outside the disclosure rules. Only about 650 contributors hit the aggregate limit in the 2012 elections in any case, according to CRP.

“It’s not going to be quite the game changer that some people think on either side, because there aren’t that many people ‘maxing out’ already,” says Bradley Smith, a former FEC chairman who heads the Center for Competitive Politics, which advocates less regulation of campaigns. Still, Smith adds, “it will make a difference.”

The chief difference will be to free candidates, party leaders and elected officials to solicit much larger checks — and to rob their contributors of the excuse that they have “maxed out” under the now-defunct aggregate limits. It remains to be seen whether “super” campaign funds will collect donations as large as $3.6 million — or whether, as Alito predicts, that turns out to be a “wild hypothetical.” But at the rate joint committees are proliferating, it won’t take long to find out.

'Max PACs' Poised to Exploit Supreme Court Decision on Campaign Finance

FOR FURTHER READING: McCutcheon decision, CQ Weekly, p. 577; outside groups, 2013 CQ Weekly, p. 2030; McCutcheon arguments, p. 1544; Citizens United ruling, 2010 Almanac, p. 11-35; soft money ban (PL 107-155), 2002 Almanac, p. 14-7.