CQ WEEKLY – IN FOCUS

Sept. 11, 2014 – 5:39 p.m.

Obama’s Rules of Disengagement

By Jennifer Koons, CQ Staff

Determined to relinquish the role of the Middle East’s cop on the beat, the United States under

|

||

|

For fear of repeating the mistakes of the George W. Bush administration, Obama has tried to avoid any further entanglements in the region. But that disengagement may have backfired.

Absent a clear policy for advancing democracy in the region, the United States has been forced into an ad hoc firefighting role, without ever extinguishing the root causes of the flames.

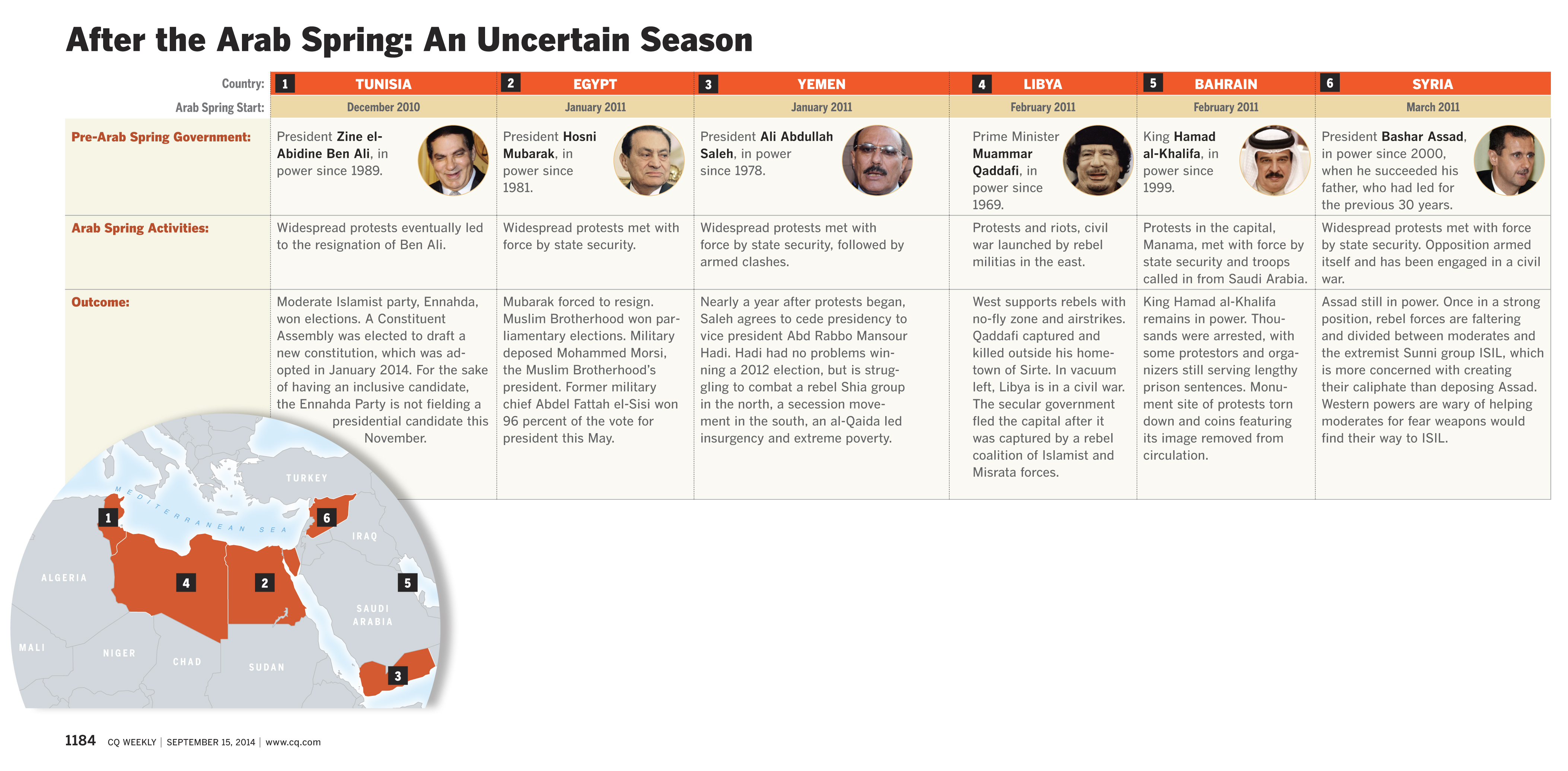

Gone is the optimism that accompanied a 2011 wave of democratic uprisings in the region, as new regimes have faltered or failed. In Iraq, for example, bungled leadership left a power vacuum that radical Islamic extremists have swooped in to fill. A series of conflicts have broken out between extremists and secularists who sympathize with the Middle East’s former regimes.

“These problems haven’t just emerged out of nowhere in the past month,” says Amy Hawthorne, a resident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and a former State Department senior adviser in the Office of the Middle East Partnership Initiative during the Arab Spring. “They’ve been building and building until they finally erupted.”

The rise of the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq — after the vicious civil war in Syria and the 2012 terrorist attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya — poses a critical test of Obama’s Middle East and North Africa policies, as the president tries to rally regional allies to beat back the militants. The new strategy may require a shift away from Obama’s policy of restraint, which was formulated to counteract a democracy-by-force philosophy that he perceived as a hallmark of the Bush administration.

With the president’s approval ratings sinking lower, and the administration weakened by years of battle with Republicans and a series of domestic and international crises, winning support abroad and at home for a new strategy could prove very difficult.

Perhaps nothing demonstrated that hands-off approach better than the U.S. response to the disparate internal uprisings that spread from Tunisia to Syria in 2011. While Obama offered rhetorical support to pro-democracy movements that brought down authoritarian regimes in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, critics say the United States offered little in practical support, including economic and humanitarian aid and security support.

Congress rejected the administration’s budget request for a fund to promote economic development in Arab Spring countries.

“Obama’s reaction has been to take quite a light touch, and now with ISIS there’s yet to be a positive strategy of economic and political change to go along with the counterterrorism strategy,” Hawthorne says. “If we could point to one common factor that is fueling each one of these crises in the region, it is a crisis of governance and political legitimacy. That’s the root cause that should be addressed.”

Taking a more direct role could be easier said than done. Defenders of the president’s approach say his restraint recognizes the reality that the United States cannot control events in the turbulent and complex Middle East.

“I think it’s no longer the duty of the United States to get involved unilaterally to try to protect these countries,” says Haleh Esfandiari, director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington. “The neighboring countries have to get their acts together and have to work with the United States to put order in their houses — be it in Libya, Yemen, Iraq and Syria. Except writing checks, what have countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar done? Do they write the checks to the right people? I have no idea.”

Obama’s Rules of Disengagement

Nonetheless, Obama’s plan to defeat the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq (also known as ISIS or ISIL), which he laid out in a televised address to the nation on Sept. 10, hinges largely on the support of these same regional players.

Rhetoric vs. Reality

During the early days of his presidency, Obama expressed support for democracy in the Middle East. In a May 2011 speech at the State Department, he compared Arabs protesting their repressive regimes to Rosa Parks and “those patriots in Boston who refused to pay taxes to a king.”

|

||

|

He spoke of a “historic opportunity” to expand U.S. policy beyond the set of core interests that the United States had pursued for decades, namely: countering terrorism and instability in the region, curtailing the spread of nuclear weapons and trying to facilitate peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

“We have the chance to show that America values the dignity of the street vendor in Tunisia more than the raw power of the dictator,” the president said, adding: “There must be no doubt that the United States of America welcomes change that advances self-determination and opportunity.”

Obama made similar remarks in his much-touted 2009 speech in Cairo, when he expressed an “unyielding belief” that all people yearn for free expression, self-government and the rule of law.

“Those are not just American ideas,” he said. “They are human rights, and that is why we will support them everywhere.”

Hawthorne says the president never really put action behind the strong words.

“Democracy promotion was never one of the president’s priorities when he came into office,” she says. “Before and after the speech, there was no strategy or mechanism in place to advance any of those ideas in the speech in any practical way.

“As things have unfolded, he’s been forced to react, but he’s still operating within that thought framework that we can’t affect the course of events in these countries. Instead, we can sort of respond to particular problems and kind of manage them.”

Shadi Hamid, a fellow at the Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy and author of “Temptations of Power: Islamists and Illiberal Democracy in a New Middle East,” says the administration has failed to distinguish between the “urgent” events, such as the rise of ISIS, and “important” goals, such as promoting democracy in Tunisia.

“Urgency has been used as an excuse to not think about the consequences of our actions, but those consequences are becoming apparent,” Hamid says.

Obama’s Rules of Disengagement

Stephen McInerney, executive director of the nonpartisan Project on Middle East Democracy, says Obama “did little in the way of promoting Arab Spring engagement beyond his big speech.”

“To make a shift of this magnitude,” McInerney says, “there has to be leadership from the top.”

Obama’s fiscal 2013 budget did include a $700 million request for a new Middle East and North Africa Incentive Fund, which was designed as a signature effort to create new initiatives to bolster the Arab Spring nations. Then-Sen.

House appropriators didn’t see it that way. Claiming the administration had failed to provide enough detail about the program, they zeroed out the funding. Vermont Democrat

As part of a separate effort, the State Department created the Office of Middle East Transitions, which was tasked with creating, organizing and implementing plans to provide special aid and other transition support for Egypt, Libya and Tunisia. Toward the end of last year, though, the office merged with a larger office in the Near Eastern Affairs Bureau assigned to handle foreign assistance for all Arab countries.

Short-Term Pain

In September 2012, two events — the murder of U.S. Ambassador to Libya Christopher Stevens in Benghazi and the attack on U.S. diplomatic facilities in Tunisia — became the final nails in the coffin of Obama’s hopeful rhetoric for the region. And it’s worth noting that the administration’s rhetoric didn’t produce much on-the-ground action.

“There’s before September 2012 and there’s after,” says Dafna Rand, deputy director of studies and

While the United States largely refrained from military action in the region, most notably in Syria, the White House did support NATO intervention in Libya, which ultimately led to the overthrow and death of leader Muammar Qaddafi in October 2011.

The murder of Stevens and three other Americans during the attack on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi almost a year later sparked a controversy that led to several high-profile congressional investigations into the assault and the Obama administration’s response, as well as the security measures at the Benghazi facility and other diplomatic posts. The attack also led the United States to scale back its role in Libya and focus most diplomatic efforts on new security threats.

An attack by protestors on the U.S. Embassy and U.S. school in Tunis drew less public and political attention, but had a similar impact on America’s approach to aiding Tunisia.

Before the attack, the Obama administration moved to highlight a successful democratic transition in Tunisia as critical to the success of surrounding nations. Obama singled out Tunisia for praise in his 2012 State of the Union address, and Congress approved more than $300 million in aid for economic recovery, a tenfold increase in the amount of U.S. bilateral assistance to the nation before 2011.

“The United States stood with Tunisia during your independence, and now we will stand with you as you make the transition to democracy and prosperity and a better future,” Secretary of State

Obama’s Rules of Disengagement

Clinton and Kefi talked about how the U.S. could aid the country during the transition, specifically discussing U.S. assistance in drafting Tunisia’s new constitution and in increasing employment opportunities.

“We need a plan for economic development, for jobs,” she said. “The Tunisian people deserve that.”

As in Libya, the focus shifted following the September 2012 attacks. After most non-essential diplomatic personnel were pulled out of the country, it became impossible to maintain many of the assistance programs. The restrained rhetoric from U.S. personnel during official visits to Tunisia further illustrated the change. In June 2013, Undersecretary for Political Affairs Wendy Sherman described the U.S. vision for the country as a “secure and stable partner on the world stage — a country playing a vital role in meeting regional and global challenges.”

“There seems to be this false notion that democratic progress is not part and parcel with our long-term national security interests,” says Danya Greenfield, the acting director of the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center. “Instead, we’ve adopted this policy by default that if a democracy emerges in a place like Tunisia, that’s great but it’s no longer a core component of our interests.”

Greenfield and other Middle East experts caution that this approach fails to account for the national security concerns that arise directly from vulnerable nations like Tunisia.

Ripple Effect

“What happens in Tunisia can have a ripple effect that’s either positive or negative,” Greenfield said.

|

||

|

While the country has arguably had more success than the other Arab Spring states, there remains a threat from extremist groups and a population growing increasingly restless amidst persistent unemployment and other economic concerns.

Ansar al-Shariah, the largest radical Islamist movement in Tunisia, was blamed for two political assassinations in 2013, and U.S. officials have linked the group to the 2012 attack on the U.S. Embassy.

Warning of the danger posed by Ansar al-Shariah and like-minded extremists, Tunisian President Mohamed Moncef Marzouki urged the United States to provide more support for his country’s transition. “If you don’t bet on Tunisia, you can say goodbye to democracy in the Arab world, and for a century,” Marzouki said Aug. 5 in a speech before the Atlantic Council. “And then we are going to give all the chances to the terrorists to impose their Islamic state. This is the challenge.”

At Marzouki’s request, the Obama administration is planning to sell Tunisia 12 UH-60M Black Hawk helicopters for a total estimated cost of $700 million, according to the Defense Security Cooperation Agency, a U.S. government agency that manages arms sales.

A faction of Ansar al-Shariah also operates in neighboring Libya and has been blamed for the Benghazi attack that killed Ambassador Stevens. In Libya, Tunisia, Syria, Egypt and elsewhere, the moderate Islamist politicians who were elected or gained influence after the uprisings have been sidelined by the violent agendas of ultraconservative militants, which has hurt efforts to build inclusive democratic states and bolstered the appeal of the former generals and allies of the dictators who were forced out of office.

Obama’s Rules of Disengagement

“Libya has become another site of a regional proxy battle between Islamists and non-Islamists,” Hamid says. “The rise of someone like Gen. [Khalifa] Heftar is in some ways becoming the preferred model for some of these countries.”

Heftar, who has lived in the United States and returned to Libya to fight alongside Islamist rebel groups in the uprising that toppled Qaddafi, has since waged battle against those he calls Islamic “terrorists” and derided the country’s parliament and prime minister as “illegitimate.”

Heftar has praised Egypt’s leader, former army chief Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who has led a similar crackdown on the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood, spearheading the overthrow of the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi last July.

“There are certainly parallels in Heftar’s rise and Sisi’s rise — they both use similar anti-Muslim Brotherhood rhetoric,” Hamid says. “The rise of these generals is a function of the failure of the democratic process throughout the region. In such a context, the appeal of a strongman grows for people looking for security and stability.”

Stability at All Costs

The Obama administration has demonstrated a willingness to work with both the foes and the former loyalists of the deposed Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak. For all the grand talk of democratization, the Obama administration has fallen back on the same old policy.

“Our core goal in Egypt since 2011 has been to maintain a relationship with whomever is running the country to protect core U.S. interests,” says Hawthorne, who advised the State Department on the U.S. response to Egyptian uprising in 2011. “I think the Obama administration and maybe even the president himself genuinely wanted Egypt to democratize. And had Egypt done that, our relationship with Egypt would be much, much stronger.”

Instead, the Egyptian Army deposed Morsi after many of the same pro-democracy forces that had protested Mubarak’s regime went back to the streets to oppose a power grab by Morsi.

The upheaval worried the United States, which has viewed Egypt as a strategic partner in bringing stability to the region — including the country’s peace agreement with Israel.

“The U.S. has been very worried since Mubarak’s overthrow that our special security relationship might be jeopardized, so we’ve mainly tried to protect that while urging whoever’s running Egypt to be more inclusive,” Hawthorne says. “Of course, since we haven’t really reshaped the relationship, leaders know that there will be few consequences on our end if they don’t democratize.”

Middle East experts see a similar pattern of putting short-term stability ahead of longer-term political changes throughout the region. And critics say the United States missed a unique opportunity to foster more meaningful ties to the young people in the region who took to the streets for a more democratic form of government.

Hawthorne bemoans Obama’s small-bore vision. As new governments have struggled to survive, “Why have we not done everything we can do reinforce that positive trend?” he asks. “That’s one of our greatest failures. We haven’t advanced a positive vision that’s reinforced something emerging in these societies.”

FOR FURTHER READING: U.S.-Iran relations, CQ Weekly, p. 138; tensions between Israel and the U.S., 2013 CQ Weekly, p. 2036.