CQ WEEKLY – COVER STORY

July 31, 2015 – 1:36 p.m.

Islamic State: The Focus For Now Is on the Caliphate

By Ryan Lucas, CQ Staff

As slogans go, the Islamic State’s lacks panache. It’s a bit clunky and doesn’t roll off the tongue. And worst of all, it whitewashes the bloody trail that the extremists have hacked out across the Middle East.

|

||

|

But the terrorist group’s motto, “remaining and expanding,” does cut to the core of the militants’ vision of a state that is a permanent and growing addition to the world map. It also underscores — despite the rhetoric in Washington to the contrary — that the United States doesn’t reside at the heart of the Islamic State’s universe.

One could certainly be forgiven for thinking otherwise. In one of a series of appearances on TV and at high-profile conferences, House Homeland Security Chairman

“There are calls to arms going out from Syria to the United States to activate and attack military installations, you know, attack police officers,” the Texas Republican said.

Indeed, the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, would gladly claim credit for inspiring violence in the United States, but that doesn’t mean that it’s devoting much of its time or energy toward striking the global power half a world away. It’s not.

Rather, it’s committing the bulk of its efforts — both in blood and treasure — toward sinking its roots into the territory it has seized in Syria and Iraq, building its self-declared caliphate and expanding its borders.

“There’s no question, when you look at the personnel being used, the money being spent and the fighting being conducted, the vast majority of ISIS’ efforts right now are focused on holding — or, in some cases, expanding — its presence in Iraq and Syria,” says Seth Jones, who runs the International Security and Defense Policy Center at Rand Corp. “That’s where it’s shedding most of its blood. That’s where it’s expending the vast majority of its money. And really, that’s where it’s taking on its most significant risks.”

That’s not to minimize the threats posed by the Islamic State. The group is training thousands of battle-hardened militants, destabilizing U.S. allies in the region and carving out a large swath of territory that could serve as a launching pad for future attacks. Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have blasted the Obama administration for not developing a more aggressive and comprehensive strategy for confronting it. But there is also a growing recognition that the U.S. ability to truly root out the group — which began as an al-Qaida affiliate during the U.S. occupation of Iraq, only to emerge nearly a decade later from the embers of the Arab Spring as a powerful, independent jihadi force — is uncomfortably limited.

“I think that the president has been slow to come to the realization that an air campaign without ground troops from Arab countries — I’m not calling for American ground troops — would not be effective, and it hasn’t been,” says Maine Republican Sen.

Gains and Reversals

It’s been just more than a year since the Islamic State declared its caliphate in the territory it controls straddling the Syria-Iraq border. The U.S.-led coalition has helped whittle down some of the land the extremists held at the pinnacle of their 2014 blitz, but the jihadis remain deeply entrenched.

|

||

|

Islamic State: The Focus For Now Is on the Caliphate

The front lines of the fight have ebbed and flowed over the past year, with a seesaw rhythm that has now almost grown familiar.

In Iraq, government troops, Shiite militias and Kurdish peshmerga have clawed back ground in some areas — most notably capturing the central city of Tikrit — only to lose ground to the Islamic State elsewhere, such as the Anbar provincial capital of Ramadi in May.

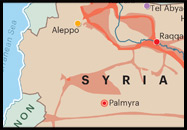

In Syria, meanwhile, Kurdish forces, backed by U.S. airstrikes, have dislodged the jihadis from much of the Turkish border, most recently pushing them out of the frontier town of Tel Abyad in June. But the Islamic State has advanced in central Syria, seizing the city of Palmyra, home to monumental ancient ruins dating back to Roman times, from Syrian government forces.

Speaking at the Pentagon in early July, President

“There will be periods of progress, but there are also going to be some setbacks,” he said.

All told, the U.S.-led coalition has conducted more than 5,000 airstrikes against the Islamic State, he said, and the extremist group has lost “more than a quarter of the populated areas that it had seized in Iraq.”

Many in Congress are pushing the Obama administration to ramp up its campaign against the Islamic State by embedding forward air controllers with Iraqi forces to increase the effectiveness of airstrikes. Others want to carve out a no-fly zone over Syria to protect civilians.

Republican hawks are adamant that even stronger steps are needed.

“Since U.S. and coalition airstrikes began last year, ISIL has continued to enjoy battlefield successes, including taking Ramadi and other key terrain in Iraq, holding over half the territory in Syria and controlling every border post between Iraq and Syria,” Senate Armed Services Chairman

His colleague,

But for now, the international campaign against the extremist group faces an uphill struggle. And the longer the militants retain their grip on parts of Syria and Iraq, the harder it will be to dislodge them, in large part because the group isn’t sitting on its haunches — it’s building a rudimentary state, home to an estimated 6 million to 8 million people.

It has set up courts and ministries to help administer the territory. It runs schools and has put together an education curriculum. It fixes bridges and power lines. It inspects markets for spoiled goods and imposes taxes.

“Initially, many of us were skeptical about it,” says Fawaz Gerges, director of the Middle East Center at the London School of Economics and the author of an upcoming book on the Islamic State. “But more than a year later, it’s still there. It has established what they call rudimentary infrastructure and institutions — in terms of taxation, services, schooling, day care, garbage collection. And the longer the Islamic State continues to exist, the more established these institutions will become.”

Islamic State: The Focus For Now Is on the Caliphate

And, as states do, it is looking toward the future. It is grooming a generation of children at training camps that include everything from religious indoctrination to weapons training.

“It’s not a terror group in the way that we understand a terror organization. It’s a state,” a former U.S. ambassador to Syria, Robert Ford, tells CQ. “I think that’s one of the things that’s not understood in Washington here very well: There is a bureaucracy, and it’s not just angry Baathist colonels and generals — I mean there is that element to it — but it’s a lot of midlevel employees.”

Running this rudimentary state, including its military forces, takes money, of course. And, in this regard, the Islamic State group truly does set itself apart from traditional terrorist groups like al-Qaida.

“I don’t think we’ve ever seen a terrorist organization that had the ability to command, to draw from its own internal territory these kinds of resources,” Daniel Glaser, a senior official at the Treasury Department, told the Aspen Security Forum in late July. “It’s truly unprecedented, the resources that ISIL can derive just from the territory they control.”

He ticked off the Islamic State’s primary sources of revenue: banks, extortion or taxation, and oil.

Burning Through Money

The group plundered between $500 million and $1 billion from two big state-owned banks in Mosul as well as some 90-odd private banks that have branches in Islamic State-held territory, Glaser said.

“The good news is that’s nonrenewable. Once they burn through that money, that’s money that will not be available to them anymore,” he said.

The group also brings in hundreds of millions of dollars a year by taxing or extorting government salaries and general commerce, he said. Illicit oil sales are the group’s third financial pillar. Glaser said the group made around $40 million in one month earlier this year from the sale of oil.

While the Islamic State’s focus is on its core territories, the group holds an expansionist vision and an expansionist creed. It has established “affiliates” in a handful of countries stretching from Pakistan in the east to Nigeria in the west.

The nature of these affiliates varies from case to case. Boko Haram in Nigeria and Ansar Beit al-Maqdis in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, for example, were previously known jihadist groups that pledged allegiance to the Islamic State and its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

In Yemen and Afghanistan, it appears to be clusters of extremists who have aligned themselves with the Islamic State, although there aren’t reliable numbers for either country.

“These affiliates are not emerging from nothing. They are part of more localized insurgent movements that aim to enhance their legitimacy versus other rival insurgent groups or against the government they are fighting,” says Ramzy Mardini, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council. “These alliances are a matter of beneficial reciprocity: The local affiliate group gains legitimacy and prestige from the global jihadist movement, perhaps some material support, and the Islamic State gains the propaganda value that its reach and influence is expanding.”

Islamic State: The Focus For Now Is on the Caliphate

Two of the most active affiliates are in Libya and Egypt’s Sinai.

In Libya, where the group has declared three “provinces,” the militants made their mark with a gruesome 15-minute video showing the beheading of 21 Egyptian Coptic Christians on a beach along the Mediterranean Sea.

In Egypt, meanwhile, the Sinai Province of the Islamic State has carried out a wave of attacks against security forces. In one deadly, coordinated assault in northern Sinai on July 1, the militants attacked several military checkpoints before occupying the town of Sheikh Zuwaid for hours.

One of the lingering questions is the degree of coordination between the Islamic State leadership and its various affiliated groups.

In the case of Libya and Sinai, there has been little indication of significant movement of manpower from the Islamic State’s core in Iraq and Syria, according to one congressional aide familiar with intelligence reports.

The aide, who spoke on condition of anonymity in order to discuss counterterrorism efforts, says the Islamic State’s leadership does communicate with its affiliates, but the degree of command and control remains murky.

For the Islamic State, the branches help push the narrative of continued expansion while also burnishing its credentials — both of which boost the group in its rivalry with al-Qaida.

“AQ and IS are in competition for being the leader of the global jihadi movement,” Mardini says. “The Islamic State needs to demonstrate to their audience that it has followers, and these pledges from local insurgent groups help in that regard.”

Where does all this leave the United States in the Islamic State’s eyes? Down the priority list.

The group has ramped up its rhetoric against the West since the start of the international airstrikes against it last August, denouncing what it calls a doomed “crusader” campaign. It has also put a greater emphasis on exhorting supporters who cannot travel to Syria and Iraq to join the group to carry out attacks in the West instead.

“They want people to be killed in their name. And they’re coming to us with that message with their propaganda and their entreaty to action through Twitter and other parts of the social media,” FBI Director

But Comey made an important distinction between al-Qaida and the Islamic State.

Al-Qaida conducted multipronged, intricate attacks with carefully vetted operatives. Those plots took time, training and money. The Islamic State, in contrast, is merely urging its supporters in the West to pick up a gun and shoot somebody. There’s no investment, to speak of, other than in propaganda.

Islamic State: The Focus For Now Is on the Caliphate

Collins agrees that the Islamic State threat is an “inspirational” one — for now.

“They want to establish the caliphate first,” she says, “but I don’t think their ambitions are going to end with the establishment of the caliphate.”