CQ WEEKLY

Sept. 28, 2013 – 6:47 a.m.

Smaller, but Smarter: The Military's Chance to Remake Itself

By Frank Oliveri, CQ Staff

Ever since January 2011, when Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates announced plans to find $100 billion in budget cuts over five years, hawks in Congress and military leaders have been warning that Pentagon spending simply couldn’t be cut more without damaging the U.S. military.

|

||

|

Those warnings have grown only louder and more ominous since the Obama administration proposed additional cuts and Congress imposed austere spending caps over a 10-year period, enforced by a sequester mechanism.

Last month, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Raymond T. Odierno told the House Armed Services panel that the Army would “struggle to even meet one major contingency operation” — and nobody challenged the assertion.

Panel member

Under current law, the Pentagon has to reduce its planned spending by $500 billion over 10 years, on top of $487 billion in cuts the department previously accepted. That means that, excluding war-related accounts, defense spending is set to decline by about 10 percent between its peak in fiscal 2012 and fiscal 2014. And starting in fiscal 2015, the spending caps allow the budget to begin rising again.

With the military still set to spend roughly $5 trillion over 10 years, former military and civilian leaders, lawmakers and congressional staff say national security does not have to be compromised. They agree that while the overall force would be smaller and likely more reliant on the National Guard and reserves, it would be more highly skilled and still be able to exert superiority on land, air, sea and space.

A successful transition, however, hinges on whether Congress and the Pentagon can manage the cuts and trim bloated overhead spending to allocate a greater share to war fighters. By spending more wisely, some defense experts say, the Pentagon could recapture a large part of the $500 billion the deficit reduction law mandates it must reduce from future plans.

That will certainly be more difficult if Congress and the president are unable to craft budgets that get anywhere close to the spending caps, thereby triggering indiscriminate sequester cuts through fiscal 2021. It would also require some painful decisions by policymakers on both sides of the Potomac River, and to date lawmakers and military leaders have shown an aversion to even discussing how to make cuts.

“Both political parties fear being tarred as the first one to cut defense, even though the decision to cut defense was taken” with the imposition of spending caps and sequestration, the nonpartisan Stimson Center think tank noted in a report last week. “Congress also fears taking the steps necessary to put the Defense Department on a healthier institutional footing because to do so would require changing policies and programs that some of its constituents and special interest groups fight hard to keep — like pay, benefits, weapons programs and bases that support local communities economically.”

Rep.

“We’ve got nine and a half more years to go of sequestration if we don’t do something about it,” he said.

Downsizing

Smaller, but Smarter: The Military's Chance to Remake Itself

The benefits of acting early to shape the cuts would be significant. A strategically slimmed-down military would have a smaller overseas presence, with a more pronounced Pacific slant, according to defense experts. It would have a significant expeditionary capability, deeply dependent on interconnected, highly technological weapons and platforms.

Special-operations forces would become a more significant share of the overall force, and a robust nuclear deterrent would remain a linchpin of U.S. alliances in Europe and the Pacific, as well as a bulwark against existing nuclear competitors and nuclear-aspiring enemies. Meanwhile, the National Guard and reserves would serve as a strategic hedge, enjoying a greater ratio of ground forces, more capable and better trained than in the past.

“The force you end up with 10 years out is still the only force that can fly everywhere, sail everywhere, and deploy everywhere,” says Gordon Adams, a defense budget expert with the Stimson Center. “It is the only force that has global installations, logistics, intelligence, communications and transportation. Nobody else is trying to do that. The force we are talking about continues to be a globally dominant force.”

Certainly, many things could change in a decade — few people foresaw the force of remotely piloted vehicles used by the military now — but by reducing non-war-fighting overhead costs and addressing military pay and deferred pay and benefits, including health care, the U.S. military could remain pre-eminent in the world.

“In my judgment, it is the missing piece in most of the reforms that are being talked about,” Adams says.

Opportunities for Change

One step the Pentagon has taken toward reimagining itself is Defense Secretary

|

||

|

“We have to get more out of the money we spend,” says Texas Republican Rep.

Failure to do so means deeper cuts to “investment, modernization and force structure, which we don’t want to do,” Deputy Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter warned the House Armed Services panel Aug. 1.

The SCMR certainly wasn’t able to mitigate all the effects of sequestration, which stripped tens of billions of dollars from the Defense Department in fiscal 2013 and threatens to cut more than $40 billion from defense spending again in fiscal 2014. Officials examined three scenarios — one based on President

“The basic trade-off is between capacity — measured in the number of Army brigades, Navy ships, Air Force squadrons, and Marine battalions — and capability — our ability to modernize weapons systems and to maintain our military’s technological edge,” Hagel said in unveiling the SCMR’s findings.

Even so, Odierno told the House Armed Services Committee on Sept. 18 that the SCMR was built on some “rosy” scenarios in order to make a $500 billion cut over 10 years feasible.

Smaller, but Smarter: The Military's Chance to Remake Itself

In terms of savings, the SCMR broadly outlines certain information technology changes that could be made to save money. Hagel announced he would initiate a phased 20 percent budget reduction for the office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff and service headquarters. The plan targets 20 percent in budget reductions, but it also sets as a goal a 20 percent reduction in personnel.

The SCMR report also called for savings to be found in compensation and benefits, areas of the budget that have ballooned over the past decade at an unsustainable rate. But this has long been an area that lawmakers are loath to touch.

The SCMR proposed decreasing the size of the Army from a minimum of 490,000 to 420,000. It would reduce the size of the reserves from about 550,000 to 490,000, and Air Force tactical squadrons by five.

A full sequester, however, would drive the Pentagon to consider even deeper cuts, such as reducing aircraft carrier strike groups, amphibious ships and older Air Force bombers and fighters, while protecting investments to counter anti-access and area denial threats, such as the family of long-range-strike systems, submarine cruise missile upgrades and the Joint Strike Fighter. Cyber and special-operations forces would still be a top priority. The Army could come down to as low as 380,000, and the Marine Corps, from 182,000 to as low as 150,000 troops, according to some proposals. The second choice would be to protect force size but trade away high-end capability.

“Another cut, and another cut, and then you are deep in the muscle of the military,” Thornberry says.

Not surprising, the report had its critics. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington, called it “dangerous,” saying it “presents no real or rational choices for preserving necessary U.S. military capabilities.”

But others say the report didn’t go as far as it could have.

The first major benchmark of this new era will be the fiscal 2015 budget submission expected in February. Unlike recent years, where military officials submitted budgets with the hope that budget caps would be cast aside, the fiscal 2015 submission is expected to more seriously address the fiscal limitations under law.

Painful Redistribution

No matter how the Pentagon budget ends up being cut, the Army is almost certain to take the biggest hit.

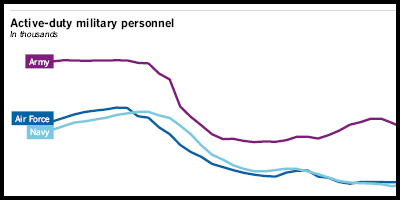

Odierno told the House Armed Services panel Sept. 19 that between fiscal 2014 and fiscal 2017 the Army will draw down its forces and continue to have degraded readiness and extensive modernization program shortfalls. Under the current plan, the active Army will fall from a wartime high of 570,000 to 420,000 and the Guard and Reserves from 563,000 to 500,000 by fiscal 2023, he said.

But if sequestration is fully implemented, he warned that the Army will not be able to “fully execute” the Pentagon’s current strategic objectives.

“We’ll be required to end, restructure or delay over 100 acquisition programs, putting at risk the ground combat vehicle program, the armed aerial scout, the production and modernization of our other aviation programs, system upgrades for unmanned aerial vehicles, and the modernization of our air defense command-and-control systems, just to name a few,” Odierno said.

Smaller, but Smarter: The Military's Chance to Remake Itself

The Air Force and Navy made similar claims regarding the military’s strategic objectives, while the Marine Corps said it could meet its requirements, but just barely.

The Marines could come down from 182,000 strong to as low as 155,000, depending on whom one asks, but Marine Corps Commandant Gen. James F. Amos said anything fewer than 174,000 would be dangerous.

“I think we are likely to see total active-duty end strength drop by another 100K to 200K over the next five years or so,” says Todd Harrison, a defense budget analyst with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Analysis. “A disproportionate share of that is likely to come from the Army, since it has not yet found a compelling strategic narrative for why it needs half a million soldiers once we are out of Afghanistan.”

The Air Force and, particularly, the Navy will likely see the smallest reductions. Experts say their roles in the Obama administration’s pivot to the Pacific are better defined.

“Let’s put on the table what our needs are and then divide the pie” among the services, says Forbes, who chairs the House Armed Services seapower subcommittee. “I think when you do that it will lead to a bigger share of the pie for the Navy.”

Furthermore, domestic politics and pressure from allies will necessitate a smaller U.S. military footprint abroad, underscoring the need for an expeditionary force, Harrison says.

But there are skeptics, such as Odierno and former Pentagon Comptroller Dov S. Zakheim, who believe funding priorities must change, or the United States must reduce its role in the world.

“At some point, this is going to have to change,” Zakheim says.

Odierno said he was not an alarmist, but a realist. “Today’s international environment and its emerging threats require a joint force with a ground component that has the capability and the capacity to deter and compel our adversaries who threaten our national security interests,” he said. “The Budget Control Act and sequestration severely threaten our ability to do this.”

Odierno explained that sequestration in fiscal 2013 forced the Army to push about $600 million in depot work, maintenance and training into fiscal 2014. With another sequestration round looming for fiscal 2014, those bills will only build.

“By the end of FY ’14, if that occurs, 85 percent of our Army brigade combat teams are now unready because of this continued pressure on our budget,” he said. “My biggest fear, actually what keeps me up at night, is I have to — I’m asked to deploy soldiers on some unknown contingency and they are not ready.”

With the president again deciding to exempt personnel from a potential fiscal 2014 sequester, operations and maintenance and modernization accounts would absorb the brunt of the cuts. In fiscal 2013, those accounts took about 96 percent of the impact of sequestration, according to retired Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Arnold L. Punaro, a member of the Defense Business Board.

The CSBA earlier this year conducted a survey of think tanks in Washington from across the political spectrum. Each team — the American Enterprise Institute, the Center for New American Security, the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the CSBA — saw significant cuts to ground forces.

Smaller, but Smarter: The Military's Chance to Remake Itself

But most experts agree that reductions to the Army should come with a hedge: a robust guard and reserve force.

“The big piece is the ground force gets smaller and the call-up capability is the guard and reserves,” Adams says. “You build in capability in the guard and reserves, which at this point is pretty ready. Ten years out, it won’t be, so you need to configure training differently than we do now. They will have to do more real training, not two weeks in the summer.”

Certainly, the Navy and Air Force would also lose manpower, but most experts agree these forces must be modernized. The think tanks emphasized investments in stealth — although fewer fighters, attack aircraft and bombers overall — cyber, special operations and robotics, while seeking fewer surface combatants, including aircraft carriers, and ballistic missiles. They all projected cuts in readiness accounts.

“We are on a fiscally unsustainable path,” says retired Marine Corps Gen. James N. Mattis, former commander of U.S. Central Command. “It does no good to have a military that adds to that fiscal instability. We have to do some real strategic thinking, because we are going to do less with a smaller military, but we must not do it less well.”

Controlling Overhead Costs

One of the only ways in the current budget climate that the Pentagon could preserve force structure and modernization is by finding significant savings and efficiencies in its current operations.

|

||

|

It would appear, according to Adams, who once oversaw defense spending accounts in the Office of Management and Budget during the Clinton administration, that the military still has much work to do.

In recent years, the Defense Business Board in several reports showed that the Pentagon’s overhead represents, as a share of the overall defense budget, about 42 percent.

That number, says Punaro, is well in excess of all business norms. Punaro says the department has failed to establish adequate controls to keep overhead in line relative to the size of the force. As a result, overhead work exploded, in particular among contractors.

“There is a sizable portion of the military who are performing both inherently governmental and non-inherently governmental work that could be more appropriately assigned to DoD civilians,” he said in 2010 as the chairman of a Defense Business Board task force. “The military are compensated at rates substantially greater than their civilian counterparts but, more importantly, they are needed at the tip of the spear.”

Given the huge amount of overhead costs, Punaro says Congress and the Pentagon must better understand their effect on Pentagon budgeting. “No business leader could manage a major enterprise without knowing the ratio of overhead to output,” he says.

The problem is so great for the Pentagon that it has, in certain cases, 50 percent less buying power now than during the Carter administration, despite having far more money, Punaro says.

Smaller, but Smarter: The Military's Chance to Remake Itself

Headquarters costs have risen at alarming rates, particularly in defense agencies and the office of the secretary of Defense, but also in the combatant commands and the services themselves, Adams says.

“If you don’t fix the back office, the size of the force will be smaller, the deployment cycles of the force will be more interrupted and with gapping, the overseas infrastructure will probably be thinner, and the hardware choices will be more draconian because you are spending an awful lot of money just plain minding the store,” Adams says.

The report released last week by the Stimson Center recommends headquarters reductions, defense agency reductions, savings in training, removing military people from inherently nonmilitary jobs, reductions in civil servants and contractors, changes in retirement and health benefits, and other actions. These would save a total of about $22 billion annually.

Most of the money at issue is buried inside the Pentagon’s giant operations and maintenance accounts. Adams says about 60 percent of the operations and maintenance accounts are tied to non-combat-related infrastructure, while 40 percent can be linked — “but not certainly” — to readiness.

“While it is fine that Hagel wants to take 20 percent from headquarters over five years, that’s not really where the problem is,” Adams says. “It’s the fat marbling the services’ infrastructure.”

To illustrate the problem, he points out that while there are roughly 1.3 million uniformed personnel in the active military, there are more than 1.5 million civilians and contractors working for the Pentagon.

“There is something wrong with that,” Adams says.

Former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Gary Roughead agrees but was more critical of the reliance on contractors.

“We really have corrupted our thinking,” he says. “I’m not talking about contractors producing things. I’m talking about the folks that are sitting around the wall in all the conference rooms taking notes.”

He says that when contracts end, he has noticed an unfortunate tendency by the Pentagon to try to keep an individual around.

“When the time comes and the job is over, it is time to move on,” he asserts.

As for civil servants, the Pentagon usually loses about 12 percent annually — between 70,000 and 90,000 people — through retirements, departures or terminations.

Using that as a baseline for a force management plan, Pentagon managers could pull together buyout and bonus packages and achieve significant savings in civil servants alone.

Smaller, but Smarter: The Military's Chance to Remake Itself

Punaro adds that personnel and benefits costs, including health care, must be reduced. He says the Pentagon is paying people in terms of benefits for 60 years, for 20 years of military service.

“In two years, the cost of retired pay and health care for retirees and dependents will exceed the entire appropriation for active-duty, Guard and Reserves military personal accounts, so this is the problem,” Punaro says.

Enough could be saved to offset most of the cuts imposed by the deficit reduction law.

“We ought to be able to get $300 [billion] to $400 billion over 10 years,” Adams says.

But failing to achieve those savings could undermine the military’s ability to meet its strategic requirements, as the services chiefs recently said.

“We’re in a death spiral right now in terms of military capability,” Punaro says. “And by the way, sequester doesn’t do one scintilla to address these problems; in fact, it makes them worse.”

FOR FURTHER READING: Sequester likely in fiscal 2014, CQ Weekly, p. 926; fiscal 2013 spending measure (PL 113-6), p. 580; debt limit law (PL 112-240), p. 83; 2011 debt limit law (PL 112-25), 2011 Almanac, p. 3-11. The Stimson Center report is at http://www.stimson.org/images/uploads/Strategic_Agility_Report.pdf.